In May 2024, a low key regulatory change set up what may become Europe’s next default login. The updated European Digital Identity Framework, widely known as eIDAS 2, entered into force on 20 May 2024. It requires every EU member state to offer at least one official EU Digital Identity Wallet to citizens and residents by 2026, built to common technical specifications.

The idea is simple to describe and complex to deliver. Instead of juggling different logins, scans and apps for each bank, university or public service, people will be able to prove who they are and share specific credentials from a wallet on their phone. By 2027, large online platforms, banks, utilities and other key sectors are expected to accept the wallet, and the EU’s longer term goal is that 80 per cent of citizens use some form of digital identity by 2030.

For most readers, this will not feel revolutionary on day one. There will still be passwords, plastic cards and slow systems. But as wallets roll out, they are likely to change how we apply for bank accounts, rent flats in another country, enrol on a degree or start a new job. They also raise questions about who controls data, how privacy is protected and what happens if you lose your phone. For UK users, the wallet will sit alongside national projects such as the planned GOV.UK Wallet, creating a new landscape for cross border identity.

What is the EU Digital Identity Wallet, really?

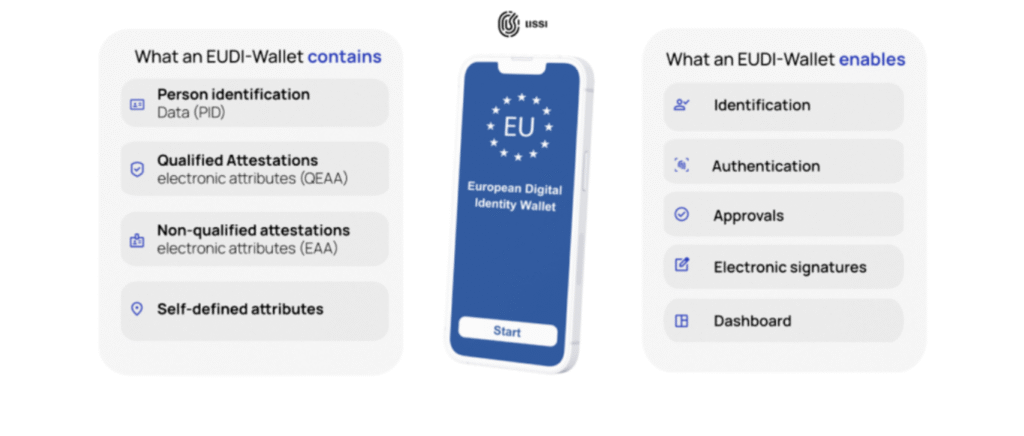

Despite the name, this is not a crypto wallet and it does not store money. The EU Digital Identity Wallet is a secure app or system that lets people store, manage and present verified digital credentials, such as their national ID card, driving licence, degree certificates, professional licences, prescriptions or electronic signatures.

The wallet sits on top of the broader eIDAS 2 framework, which governs electronic identification and trust services in the EU. Under the new rules, each member state must provide at least one certified wallet, recognise wallets from other member states and meet strict security and interoperability standards. The regulation requires “privacy by design”, so wallets must be built to minimise data sharing and give users control over which attributes they disclose.

In practice, a wallet will not hold raw images of your documents in the way a photo album does. It will contain cryptographically signed credentials issued by trusted authorities. When a service asks for proof of age, for example, you can share a yes or no answer rather than your full date of birth and address. When a university checks a qualification, it can verify a digital diploma rather than relying solely on a PDF.

At the same time, the wallet is meant to work offline as well as online. Some proposals include the ability to present QR codes or short lived tokens in face to face situations, such as proving your entitlement to a discount or access to a building.

At a glance

The EU Digital Identity Wallet is a state backed app that stores verifiable credentials, not money. It is built on strict eIDAS 2 rules for security, interoperability and privacy, and should let users share only the minimum data necessary for each interaction.

From KYC checks to renting flats: how wallets change onboarding

Where this becomes tangible is in onboarding, the catch all term for everything from opening a current account to registering for a master’s degree. Today, many of those processes still rely on a mix of scans, manual checks and repeated forms. Banks and fintechs have to comply with know your customer (KYC) and anti money laundering rules, universities need to verify identity and prior qualifications, and landlords or employers want to see proof of address and status.

The wallet is meant to cut down that friction. The European Commission explicitly cites use cases such as opening bank accounts, enrolling at a university abroad or applying for jobs as core scenarios. Instead of uploading separate documents, a customer could consent to share specific verified attributes directly from their wallet. In theory, that should speed up compliance checks and reduce the risk of forged documents slipping through.

When people still upload scans of old paper certificates, HR teams will not stop doing basic hygiene checks. A common pattern is to run those legacy scans through a simple photo quality enhancer to clean shadows, sharpen text and make seals legible before they are checked against the wallet data in the background. In this model, the wallet becomes the primary trust anchor, while document images are treated as a useful but secondary signal.

The same applies to renting a flat in another EU country. At the moment, a prospective tenant might email copies of their passport, contract and payslips to an agent they have never met. With wallets, agents and landlords should be able to request a standardised set of proofs, such as identity, employment status and income range, presented directly from a trusted source. For cross border workers or students who already juggle multiple bureaucracies, that kind of standardisation could be transformative.

Banks and payment providers have their own reasons to embrace wallets. Compliance teams already spend heavily on KYC, transaction monitoring and fraud prevention. Analysts argue that a common, high assurance identity layer could reduce false positives, improve risk models and simplify onboarding for legitimate customers, especially in business to business settings where organisational identities matter too. In sectors where some customers still send in scanned letters or contracts, a back office clerk may continue to rely on a photo quality enhancer to tidy up those images before they are reconciled with the structured data coming from the wallet.

At a glance

Wallets promise to replace repeated document uploads with reusable, verified credentials, streamlining KYC, university admissions, job onboarding and cross border renting, while leaving room for traditional document checks where needed.

Privacy, control and the lost phone question

A central selling point of the EU wallet is privacy. The regulation talks about “user control” and “data minimisation” in unusually strong terms for a piece of infrastructure that so many services will rely on. Users are supposed to see which attributes are requested in each transaction, choose whether to share them and maintain an audit trail of who has accessed what.

Technically, the wallet is only one part of a wider trust stack. Credentials are issued by trusted providers, and verification happens through standardised protocols, not by letting every app rummage through your phone. That creates room for selective disclosure. For example, you might share proof that you are over 18 without revealing your exact date of birth, or prove that you hold a valid professional licence without sending the full certificate.

Security questions are more complicated. Wallets must be protected by strong smartphone security, such as biometrics or local PINs, and the regulation requires open scrutiny of many wallet components to catch weaknesses early. If a phone is lost or stolen, the aim is that the wallet can be revoked and reissued, much like cancelling and replacing a bank card, with identity re verification built into the process. In parallel, critical credentials can be backed up, in encrypted form, to prevent permanent loss.

For organisations, there is a balance to strike between automation and caution. A university or employer that relies mainly on wallet data might still want to see supporting documents in edge cases. When those arrive as low quality scans, tools such as a photo quality enhancer are simply pre processing steps in a broader risk management workflow, making stamps and seals easier to check by eye while the wallet’s cryptographic evidence does the heavy lifting.

At a glance

The wallet is designed around privacy by design and strong security, with selective data sharing, revocation mechanisms and transparency about who accessed which attributes, although the real test will be how member states implement those promises.

What does this mean for the UK and non EU users?

Post Brexit, the UK sits outside eIDAS 2, and the UK version of eIDAS does not cover electronic identification schemes at all. Yet this does not mean the EU wallet is irrelevant. Any British traveller, student or business that interacts with EU services is likely to see wallet based options cropping up in the next few years, especially for high value or regulated activities.

For individual users, the interactions will fall into a few categories. British citizens living or working in an EU country may receive a wallet through their host state, letting them access local services and cross border portals more easily. UK residents who stay mainly in Britain might still encounter wallet based logins when they apply to an EU university, open an account with an EU fintech or sign up for a platform that prefers wallet proof over traditional KYC methods.

On the UK side, the government is developing its own GOV.UK Wallet, which will start by storing veteran cards and digital driving licences. While it is not directly aligned with eIDAS 2, the direction of travel is similar: a state backed app that holds official credentials and can be presented to both public and private services. Over time, pressure to ensure some degree of interoperability, or at least mutual recognition in specific sectors, is likely to grow.

For non EU businesses that sell into the single market, the impact is more strategic. Regulators and analysts point out that providers offering services in the EU will be expected to accept wallet based identities where sector rules demand “high” or “substantial” assurance, even if they are headquartered elsewhere. That means UK banks, insurers, recruiters and platforms with EU customers may need to integrate wallet acceptance into their onboarding flows, alongside their own digital identity solutions.

At a glance

The UK is outside eIDAS 2 yet will still feel the wallet’s effects, as EU users arrive with portable credentials and UK firms serving the bloc are nudged to accept them, while national projects like GOV.UK Wallet develop in parallel.

Conclusion

The EU Digital Identity Wallet will not abolish passwords overnight, and it will not erase every form or scan currently clogging up HR and compliance workflows. What it offers instead is a slow, structural shift. By 2026, every EU member state will have at least one wallet scheme. By 2027, key sectors will be expected to accept it. By 2030, Brussels hopes that four in five Europeans will be using digital identifiers of some kind in their daily lives.

For individuals, that should mean fewer repeated uploads, more consistent logins across borders and greater visibility into who has accessed their data. For organisations, it promises cleaner onboarding, lower fraud risk and, eventually, a common way of handling identity across a fragmented continent. None of that removes the need for careful governance. Wallets will only earn trust if they are implemented with real transparency, robust security and meaningful redress when things go wrong.

From a UK perspective, the wallet is best seen as part of a broader global trend towards state backed digital identity. Whether or not Britain chooses to align closely with eIDAS 2, British users and businesses will be dealing with EU wallet holders as customers, employees and partners. Understanding how the system works, and where tools like document enhancement fit into the workflow, is no longer a niche compliance concern. It is becoming a basic piece of digital literacy for anyone who moves, studies or does business in and around Europe.

FAQ

Is the EU Digital Identity Wallet a kind of cryptocurrency wallet?

No. Despite the name, it does not store money or crypto assets. It stores verifiable digital credentials such as ID cards, licences and diplomas that can be presented to services under the eIDAS 2 framework.

When will people in the EU actually be able to use these wallets?

The regulation entered into force in May 2024. Member states must offer at least one certified wallet by 2026, and key sectors, including banks and very large platforms, are expected to accept them from around 2027 onwards.

What happens if my phone with the wallet is lost or stolen?

The rules require strong security, the ability to revoke and reissue wallets and options to back up credentials securely. Losing a device should not mean losing your identity, but exactly how revocation and re enrolment works will depend on each national implementation.

Will UK citizens be able to get an EU Digital Identity Wallet?

UK citizens who live, work or study in an EU member state may be eligible for that state’s wallet scheme. UK residents who remain in Britain will mainly encounter wallets as a login method offered by EU services, for example when applying to a university or opening an account with an EU based provider.

Do UK businesses have to support the EU wallet?

There is no blanket requirement, but UK firms that have EU customers or operate in regulated sectors may find that accepting wallet based credentials becomes a practical necessity, especially where EU rules require high assurance identity checks. It is wise for cross border businesses to monitor eIDAS 2 guidance and plan integrations early.